Kenya Risk Profile

First published: April 2023

Danny Ramon

Intelligence & Response Manager

Overview

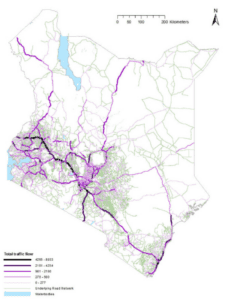

With the region’s busiest seaport and the third largest economy in sub-Saharan Africa, Kenya is the gateway to several East African states and a major export hub for agricultural products to the world. While the port of Mombasa is already the foundation of the Northern Corridor transport links to South Sudan, Tanzania and the Great Lakes region, ambitious new infrastructure projects seek to expand and improve freight movement across the country by road, rail and air. However, this vision faces challenges from ethnic conflict, cargo security, political contest and an endemic trans-national terrorist threat.

Key Infrastructure

The port of Mombasa, including Kilindini Harbour, the Old Port, Ports Tudor and Reitz as well as all Mombasa island, is the main port of Kenya and the busiest in East Africa. Serving as an entrance point to much of East and central Africa, it is the beginning of the Northern Corridor transport route to the Ugandan border at Busia and Malaba via the capital Nairobi. The port has a handling capacity of 2.65 TEUs annually and is equipped with a grain and two oil terminals as well as berths for container and bulk cargo. Construction of the second container terminal was completed under the Mombasa port development programme by a Japanese firm in May 2022, adding a further three berths to accommodate ships from 230 to 350 metres. The port has been subject to recent labour disputes, such as in November 2021 when members of the Dock Workers Union (DWU) staged a seven-day strike over pay. Linking the Port of Mombasa with the landlocked countries of the Burundi, South Sudan, and Rwanda, the Northern Corridor is the key rail and road freight link through Kenya to the Great Lakes States. The corridor suffers from extremely high levels of congestion, particularly  around Nairobi and the border crossing points of Busia and Malaba. Protests by truck drivers along the corridor route, often in the form of road

around Nairobi and the border crossing points of Busia and Malaba. Protests by truck drivers along the corridor route, often in the form of road

blocks, are not uncommon and are usually sparked by concerns over safety, excessive delays or measures such as Covid-19 testing fees. The Northern Corridor also suffers from significant cargo theft including armed hijackings, fuel syphoning and arson of transport vehicles. Measures are being considered to ease congestion at the Ugandan border with possible additional crossing points at Lwakhakha and Nadapal.

The completion of the Standard Gauge Rail (SGR) project linking Mombasa to depots in Nairobi and Naivasha led to a directive to move bulk cargo to the capital by rail, claiming cost savings and reduced congestion but sparking protests by drivers in Mombasa and a legal challenge by the Kenya Transporters Association (KTA) in

2019. Promotion of the SGR remains a contentious issue given its potential to negatively impact truckers and towns on the route from Mombasa to Nairobi, and future industrial actions or even sabotage by angered truckers of the railway is possible.

The new trans-shipment port at Lamu is the foundational project in the Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia-Transport (LAPSSET) Corridor mega-project. A Chinese company has completed the first three of a planned 23 berths. and

South Sudan via new roads, a series of airports and an oil

berths of the port have been completed, funding issues

and poor security in the region has stalled a number of

projects. Much of the planned route of LAPSSET runs

through the deprived, arid regions of the country where

inter-ethnic violence and terrorism are common, raising

questions as to the feasibility of the project

Security

Crime in the major cities of Mombasa and Nairobi originates primarily in the informal settlements with high poverty and unemployment and spills into the main business areas. Armed robberies, muggings and snatch robberies are common, with one tactic being for two criminals aboard a motorcycle to carry out robberies and use their superior mobility to escape through the heavily congested traffic. Follow-home robberies and home invasions are less frequent but still a threat. Drug trafficking is present but not especially prolific. Seizures are primarily centred around the main cities and the provinces of Nyanza on the Tanzanian border. Quantities of heroin in the

few kilogram range have been seized in recent years in Mombasa as well as occasionally cocaine, while marijuana or “bhang” is commonly found in Nairobi and along the Northern Corridor.

Cargo theft along the Northern Corridor is a constant issue, with trucks usually targeted when at rest. Local gangs have been reported as running various scams including luring drivers to stop with young women, drugging food or drink at rest

stops, creating fake diversions and often-violent hijackings. These hijackings have resulted in the deaths of truck drivers, with drivers being shot dead between Naivasha and Maai Mahiu and in Maungu.

In 2021 two drivers were also killed and eight trucks hijacked in the Mackinnon-Mtito Andei stretch of road North of Mombasa alone. The formation of the Northern Corridor Transit Patrol Unit (NCTPU) and the increased use of cargo tracking by shippers has helped bring incidents of cargo theft down from their peak in 2016, but cargo theft, fuel syphoning and associated violence continue to be a problem.

The primary terror threat in Kenya comes from the Somalia-based Islamic extremist group Al Shabaab, which is highly active in the counties of Lamu, Garissa, Wanjir, and Mandera. Al Shabaab is responsible for numerous IED attacks, ambushes,

assassinations and kidnappings as well as clashes with security forces across the North and Northwest of the country. Additionally they have carried out complex terror attacks as deep in the country as Nairobi, including the 2013 Westgate Mall and the

2019 Dustin Hotel attacks. Al Shabaab have also established a presence in the Boni National Reserve in Garissa county to better launch raids on Kenyan soil, prompting anti-terror operations by government forces. The terror threat in the Northeastern and Coastal provinces is such that road travel is regarded as highly dangerous and travel to Lamu should be done only by air. Kenya as a whole is judged to be at a

heightened risk of terrorism, with attacks often being indiscriminate and targeted at commercial or leisure areas likely to be frequented by foreigners. Intercommunal violence is also common, particularly in the deprived North and Northwest of Kenya and the coastal regions. Rival ethnic groups of mainly pastoral farmers often come into conflict over access to water and grazing pasture. In some cases such as between

the Pokot and Turkana peoples in Turkana county, these conflicts have been going on for decades and are intensifying as drought and climate change make resources scarcer, and small arms are increasingly available due to regional conflicts and weak border security. Armed cattle raids between pastoralists are a feature in rural Kenya that is often dismissed by politicians as a traditional rite of passage to mask their inability to deal with the problem. Conflict is also common between pastoralist herders and sedentary farmers, particularly along the Tana river and into the delta, where herders seek access to water while farmers seek to prevent the herdsmen destroying crops. These conflicts can become particularly acute in times of drought.

Insufficient rains throughout 2021 and into 2022 have left much of the Horn of Africa in a state of drought. The World Food Programme has warned that 2.1 million people in Kenya are facing acute food insecurity – a 34% increase since 2020. Worst affected are the counties of Baringo, Garissa, Isiolo, Mandera, Marsabit, Tana River, Turkana and Wajir, with Lamu and Kwale counties also predicted to deteriorate into crisis. As of mid-2022, around 60% of cattle is believed to have already died and the risk of conflict between pastoralist herders and farmers is regarded as high. Kenya has also been affected by the Ukraine war and ensuing sanctions on Russian exports, having imported over $400 million in fertilisers, wheat and maize from Russia in 2020. Drought and the resulting food shortages and price inflation were a significant factor driving the politics during the 2017 and 2022 elections.

Cargo theft along the Northern Corridor is a

constant issue, with trucks usually targeted wheces. The terror threat in the Northeastern and

Coastal provinces is such that road travel is regarded

as highly dangerous and travel to Lamu should be

done only by air. Kenya as a whole is judged to be at a

heightened risk of terrorism, with attacks often being

indiscriminate and targeted at commercial or leisure

areas likely to be frequented by foreigners.

Intercommunal violence is also common, particularly

in the deprived North and Northwest of Kenya and the

coastal regions. Rival ethnic groups of mainly pastoral

farmers often come into conflict over access to water

and grazing pasture. In some cases such as between

the Pokot and Turkana peoples in Turkana county,

these conflicts have been going on for decades and

are intensifying as drought and climate change make

resources scarcer, and small arms are increasingly

available due to regional conflicts and weak border

security. Armed cattle raids between pastoralists

are a feature in rural Kenya that is often dismissed

by politicians as a traditional rite of passage to mask

their inability to deal with the problem. Conflict is also

common between pastoralist herders and sedentary

farmers, particularly along the Tana river and into

the delta, where herders seek access to water while

farmers seek to prevent the herdsmen destroying

crops. These conflicts can become particularly acute

in times of drought.

Politics

Kenya held a hotly contested general election in August, with Willian Ruto – Kenyatta’s Deputy President and aligned with the Kenya Kwanza Alliance, wont with a mere 50.5% of total votes, which was challenged by the opposing candidate.. Past elections have been marred by violence and contested results. Disinformation, hate speech, and ethnic identity are common tools in political campaigning, with fake news and endorsements being spread through social media and at political rallies. Violence after the 2007 election killed around 1,000 and led to constitutional reform and ultimately greater devolution of governance to the county level. Violence is also driven by local factors and the National Cohesion and Integration Commission has worked to resolve local issues to reduce their impact on national politics. The “handshake agreement” between Kenyatta and Odinga made in 2018 has helped curb inter-ethnic violence between the Luo and Kikuyu groups in Nairobi and assuming it holds will hopefully help to reduce ethnic rivalries, at least during the election. 23 of Kenya’s 47 counties are listed as being at a high risk of violence, and Ruto appears to be making an effort to redefine identity politics according to class rather than ethnicity in a move against the dynastic politics that could lead to violence, particularly in urban areas. Voting is mainly divided along ethnic lines, as political power usually translates into greater access to resources and patronage for the government’s dominant ethnic groups at both the local and national level.